Introduction

In a previous post, I introduced Raman spectroscopy, a powerful tool for non-destructive material analysis based on inelastic light scattering. Building upon that foundation, this post delves into the advanced Raman techniques driving the forefront of materials characterization. My own experiences with Raman spectroscopy have ignited a passion for these specialized methods and their potential for ground-breaking research.

Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS)

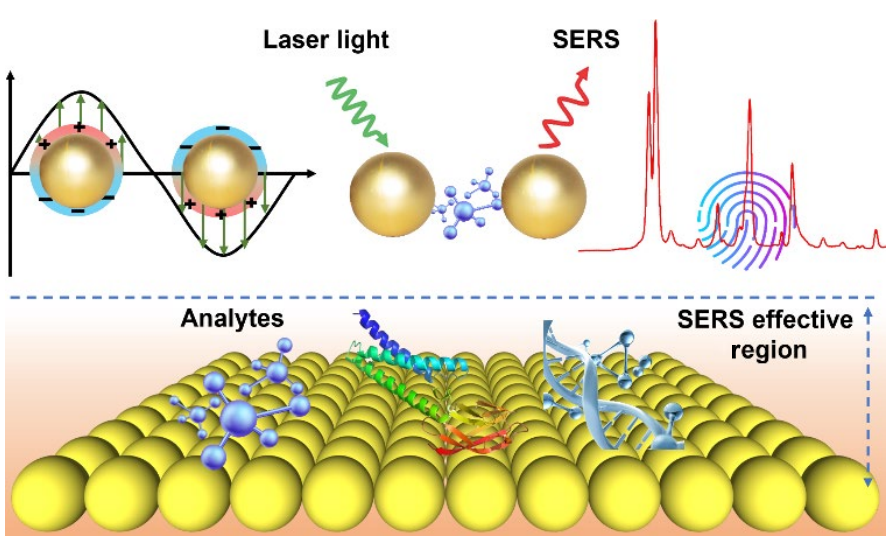

Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) offers exceptional sensitivity by exploiting the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) phenomenon on metallic nanostructures (typically gold or silver). Incident light excites these plasmons, leading to a dramatic amplification of the Raman signal from molecules adsorbed onto or near the nanostructured surface. This enables detection of extremely low analyte concentrations, down to the single-molecule level. While Raman spectroscopy itself offers sensitivity for certain solid materials, its limitations in solution-based analysis have long been a hurdle. SERS addresses this, providing an enhancement in scattering efficiency of up to 106 compared to conventional Raman scattering. This phenomenon was first observed by Fleischman et al. in 1974 [1], who reported unexpectedly strong Raman scattering from pyridine on a roughened silver electrode. Subsequent investigations by Jeanmaire and Van Duyne [2] and Albrecht and Creighton [3] demonstrated that the intensity gain extended far beyond the effect of increased surface area alone.

Images adapted from “State of the art in flexible SERS sensors toward label-free & onsite detection: from design to applications“

Mechanisms of SERS Enhancement

The SERS enhancement mechanism has two primary components:

- Electromagnetic Enhancement: The cornerstone of SERS amplification lies in the excitation of localized surface plasmons (LSPs) within the metallic nanostructure upon light irradiation. These plasmons behave as nanoantennae, generating highly localized and intense electromagnetic fields near the surface. Molecules adsorbed on or in close proximity to the nanostructure experience this enhanced field, resulting in a significant amplification of their Raman signal. The precise arrangement, size, and shape of the metallic nanostructures critically influence the LSP resonance and, consequently, the electromagnetic enhancement profile. Notably, the presence of aggregated nanoparticles creates “hot spots” – regions of particularly intense localized electromagnetic fields arising at the points of contact. These hot spots further contribute to the dramatic signal enhancement observed in SERS.

- Chemical Enhancement: A complementary mechanism to electromagnetic enhancement is chemical enhancement. This phenomenon arises from a direct chemical interaction between the analyte molecule and the metal surface. Charge transfer processes occurring at the interface can modify the electronic states of the molecule, leading to an increase in its polarizability. This enhanced polarizability translates to a stronger Raman scattering intensity. However, it’s important to note that chemical enhancement is typically limited to the first layer of adsorbed molecules directly in contact with the surface..

Applications of SERS

- Biomedical Sensing: SERS-based biosensors detect trace biomarkers, enabling early disease diagnosis, drug monitoring, and forensic analysis.

- Environmental Monitoring: Identifies pollutants at minute concentrations, ensuring water and air quality.

- Materials Science: Investigates surface chemistry, interfacial interactions, and catalytic processes with high sensitivity.

Tip-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (TERS)

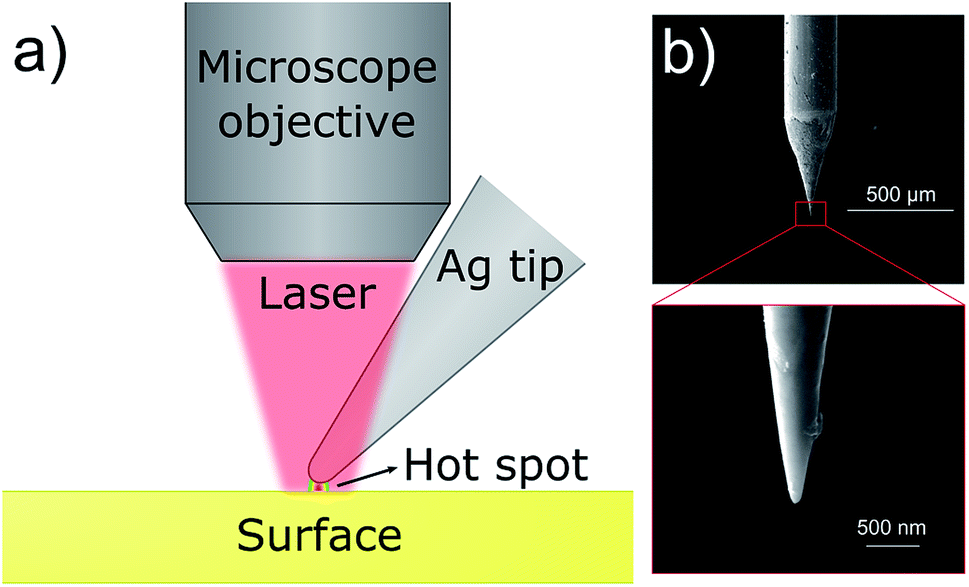

Tip-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (TERS) offers a potent marriage of Raman spectroscopy with scanning probe microscopy (SPM) technologies such as atomic force microscopy (AFM) or scanning tunneling microscopy (STM). It employs a sharp, metallic probe (typically silver or gold-coated) to serve as a nanoscale optical antenna. Positioning this probe in close proximity to the sample surface generates a highly localized electromagnetic field. This intense localization dramatically enhances the Raman signal from the molecules within the field, enabling chemical mapping with exceptional spatial resolution down to the single-nanometer scale. The concept and practical applications of TERS have been extensively reviewed [4].

Images adapted from “Development of a candidate reference sample for the characterization of tip-enhanced Raman spectroscopy spatial resolution”

TERS Mechanism

Near-Field Optics and Plasmonic Coupling:

TERS fundamentally relies on principles of near-field optics. Illumination of the metallic tip excites localized surface plasmons (LSPs), generating an intense electromagnetic field tightly confined to the tip apex. Bringing the tip within nanometres of the sample induces plasmonic coupling, further amplifying this localized field. This synergistic effect creates the source of TERS’s extraordinary sensitivity and spatial resolution.

The Critical Role of Tip Quality:

The integrity and precision of the metallic tip are paramount. Degradation during experimentation compromises spatial resolution and signal intensity. Rigorous tip fabrication methods (e.g., electrochemical etching or deposition) are essential for maximizing achievable enhancement and resolution.

SPM for Precise Distance Control:

SPM techniques provide indispensable feedback mechanisms for controlling the tip-sample distance with sub-nanometre accuracy. This precision is critical for reliable TERS operation, ensuring consistent signal enhancement.

Applications of TERS

- Nanoscale Chemical Mapping: TERS visualizes the distribution of chemical functionalities at surfaces and interfaces, providing insights into biological systems, semiconductor devices, and more.

- Single-molecule Studies: Achieves single-molecule chemical sensitivity and imaging, offering unprecedented detail in biomolecular and materials research.

- Surface and Interface Analysis: Unravels chemical composition and reactivity at the nanoscale, crucial for fields like catalysis and nanotechnology.

Impact on Research

TERS has become a transformative tool for materials research. In areas such as optoelectronic device development and nanoscale sensor design, TERS provides unmatched capabilities for investigations of strain distribution, defect localization, and interfacial interactions – all critical factors governing device performance and reliability. Its continued refinement, alongside advancements in tip fabrication and control methodologies, will further expand the reach and resolution limits of TERS. As it becomes more accessible and powerful, TERS will undoubtedly solidify its position as a cornerstone technique for cutting-edge research, driving discoveries at the frontiers of materials science and nanotechnology.

Conclusion

Advanced Raman spectroscopy offers remarkable capabilities for researchers across diverse fields. SERS provides unmatched sensitivity, while TERS reveals nanoscale chemical information. As new advancements emerge, these techniques will undoubtedly become cornerstones of materials research. Their continued development inspires me to pursue my own research and further explore their potential.

Reference List

- Fleischman, M., Hendra, P. J., & McQuillan, A. J. (1974). Raman spectra of pyridine adsorbed at a silver electrode. Chemical Physics Letters, 26, 163-166.

- Jeanmarie, D. L., & Van Duyne, R. P. (1977). Surface Raman electrochemistry part I. Heterocyclic, aromatic and aliphatic amines adsorbed on the anodized silver electrode. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry, 84, 1-20.

- Albrecht, M.G., & Creighton J. A. (1977). Anomalously intense Raman spectra of pyridine at a silver electrode. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 99, 5215-5217.

- Jiang, N., Kurouski, D., Pozzi, E. A., Chiang, N., Hersam, M. C., & Van Duyne, R. P. (2016). Tip-enhanced Raman spectroscopy: From concepts to practical applications. Chemical Physics Letters, 659, 16-24.

- Mendes, P. M., Jaculbia, R. B., Leitao, E. D., & Aroca, R. (2018). Development of a candidate reference sample for the characterization of tip-enhanced Raman spectroscopy spatial resolution. RSC Advances, 8(62), 37622-37630.

Portions of this post were refined with the assistance of Gemini Advanced AI.

If you are a researcher interested in advanced Raman spectroscopy, please feel free to connect!

Leave a comment